In the start of any chemistry class, we’re usually shown a set of weird-looking shapes called atomic orbitals. We are given a set of rules to describe them with quantum numbers n, l, m: the quantum number n is the principal quantum number that describes how much energy it has, l determines the angular momentum magnitude and hence its shape, and m determines the orientation in 3D space. We’re only told to accept this, but we never know why.

And for good reason. Knowing why requires an understanding of partial linear differential equations and a solid grasp of quantum mechanics (everyone’s favorite popsci topic). Specifically, these atomic orbitals can be derived from what is called the Schrodinger equation.

Formulated in 1925, Erwin Schrodinger published his description of the matter wave in 1926. Up to this day, this equation is still used in modern research.

Quantum mechanics, with all its weirdness, say that these atomic orbitals represent the spaces where the electrons is most likely to be found. But why don’t electrons just stay in once place? Why don’t they just orbit in a behaved manner like Earth around the Sun?

Wave-Particle Duality

Quantum mechanics assumes that matter such as electrons are both particles and waves. Wave-like properties can be seen in the patterns in the double-slit experiment, where a stream of electrons are allowed to pass through two narrow slits. The patterns seen in Figure 1 represent the interference of wave-like electrons with each other. Figure 2 shows the mechanism with how this is possible.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double-slit_experiment#/media/File:Double-slit_experiment_results_Tanamura_2.jpg

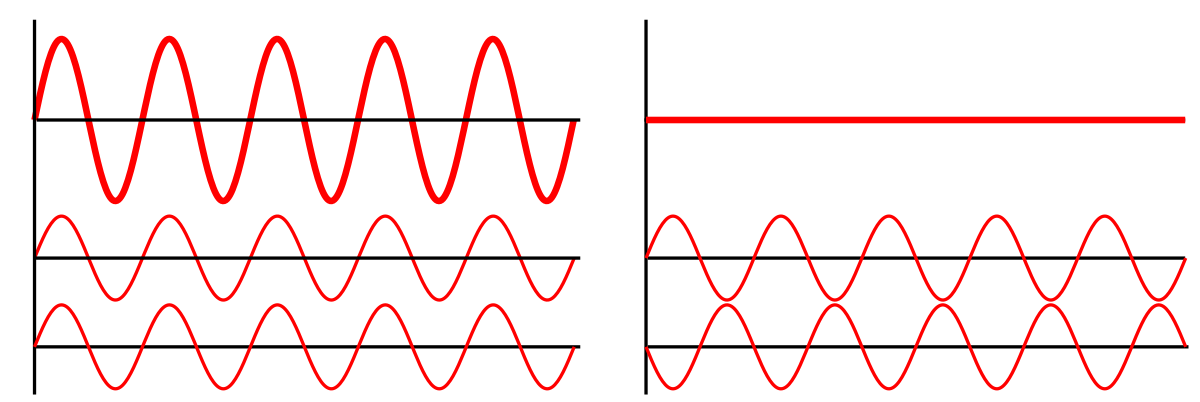

This is possible because of what’s called constructive interference and destructive interference. When two waves meet and they are exactly in phase, constructive interference happens as the amplitudes get bigger. But when they are exactly out of phase, they destroy each other’s amplitudes.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wave_interference#/media/File:Interference_of_two_waves.svg

Souce: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Double-slit.svg

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Double-slit.svg

But electrons also have particle-like properties. Light made out of photons – which themselves are both particles and waves at the same time – can knock off the electrons from a piece of metal when it’s given enough energy. To knock off the electrons, a collision must happen – something waves don’t do. As mentioned, when waves meet each other, they either constructively or destructively interfere with one another.

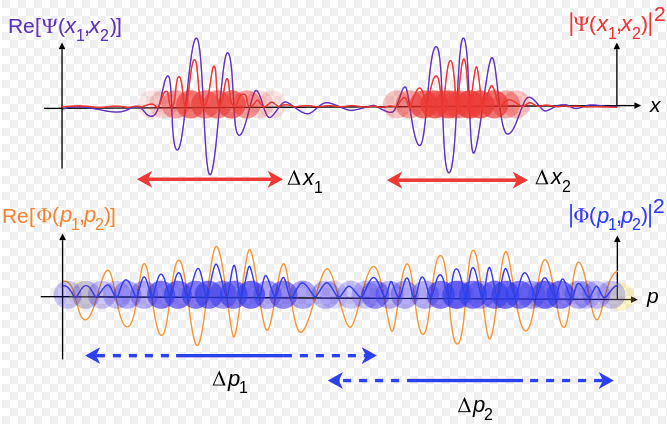

To reconcile this, physicists interpreted the wave as a sort of probability distribution of where the particle could be found. Hence, we can describe the wave as a function Ψ(x,y,z,t) – a 3D that changes over time. In particular, that probability is the square of that wave function, |Ψ|2.

This probability distribution describes where the particle is likely to be found. That’s why you’d often hear phrases such as “being at two places at the same time” – they do have chances of being found at two different position. People recognize this as the “weirdness” of QM. It would be better if we fully describe what this wave looks like.

The One-Dimensional Schrodinger Equation

In one dimension, we Schrodinger equation can be written as a function of x and t.

Where i = √-1, ħ is Planck’s constant divided by 2π, m is the mass of the wave-particle (an electron, for example), and V is the potential energy dependent on the position x.

The equation looks extremely daunting at first, but actually physicists are thankful that it’s one of the few solvable partial differential equations in the sciences. We’ll describe each part bit by bit. In the right hand side of the equation,

describes the kinetic energy of the particle, and the V(x)Ψ term describes its potential energy at a given location. We can actually have any potential energy function attached to the wave function: V(r) = (1/2)r2, V(r) = r, or V(r) = k/r2 where k is any constant. The left hand side,

describes how the particle changes with respect to time. Since the right hand side of the equation involves the addition of kinetic energy and potential energy, we can interpret it as the total energy of the particle in this case. So, we may opt to drop the left hand side and instead equation it to EnΨ to obtain

We no longer use the partial derivative with respective to x since this differential equation is time-independent.

Proceed to Part 2

4 thoughts on “Uncovering the Schrodinger Equation [Part 1]”