Computers have always been good in running several calculations at the same time. These have been useful in doing statistical computations or doing simulations. But as the number of calculations increase, the time it takes to collectively do all of them increases – in other words, it’s slower and harder to do large computations.

Understanding natural phenomena isn’t always so straightforward. Sure, we can base it off a set of theorems and laws and predict how, say, a ball of mass m follows a path through space and time. That’s easy, and most of the time we can write down a closed form formula to describe it. But the world isn’t made out of balls of mass m that can understood as a moving point.

When we take a biology class, we’re usually introduced to what is called levels of organization in life. Molecules usually serve as the simplest level, but they themselves are made out of atomic constituents that each have their electrical and chemical properties. As one goes higher in organizational level, we encounter cells which are made out of millions or billions of molecules. And cells, too, organize into tissues, then organs, and whole organisms. Eventually we reach the highest levels of organization which are ecosystems, biomes, and whole biospheres.

A system that has many individual constituents, each following a set of physical laws. But regardless if one has ten, a hundred, or a thousand molecules, they will still each follow those laws collectively. It just gets harder to compute for each of their energies, force terms, positions, and velocities. Thus, they require computer simulations that can do several calculations at the same time. But we said, as the number of calculations increase, it gets harder for the computer to process the data.

Since cells are built of almost too many molecules, it will indeed be hard to simulate an entire organism down to the molecular level. We can indeed simulate how a cell behaves by omitting their molecular constituents and focusing on the bulk of organelles, but that will force us to do numerous approximations that would lead to numerous errors. If we were to do this as accurately as possible, we must minimize the amount of approximations we do, and at best still include individual molecules in the simulation.

Molecular Dynamics

Physicists and chemists have been simulating how a group of molecules behave for a long time. These simulations often include the atomic constituents that build these molecules like lego. Even then, each atom has their own unique electrostatic and mechanical properties.

Molecular dynamics is a method for simulating said molecules. This method takes into account the potential energies and kinetic energies of each atom, which also affects their motion. These atoms can move either by vibrating, moving back and forth, or rotating. The molecule can also be affected by other factors such as the temperature of the environment, which creates random jiggling and fluctuations in movement.

Sometimes, quantum mechanics heavily affects how the body moves and interacts, since at this scale of space the wave functions of electrons around the molecule affects polarity and charge distributions.

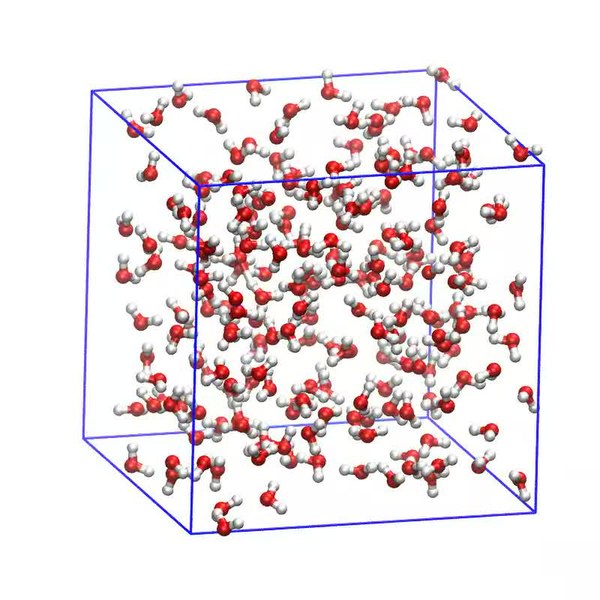

The simulation can also include other molecular bodies, either of the same chemical species or a different one. Below, we can see a simulation of water molecules. But we can also have a simulation of DNA being surrounded by water molecules, or maybe a protein folding. These can show how intermolecular forces affect the physical properties of chemicals. But these models have a catch: they are viewed in isolation, with the only external factor being temperature. In an organism’s cell, the molecules are never isolated from other chemical species.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Isothermal-Isobaric_Molecular_Dynamics_Simulation_of_Water.webm

Computational researchers usually run these simulations in a matter of seconds or a few minutes. But in reality, these happen much, much faster. A 25 second process of a protein folding might actually be representing a 25 nanosecond process. Actually, most molecular dynamics simulations model events that happen in a matter of nano to microseconds. In a way, they recreate what happens in slow-mo.

Now, as previously mentioned, the more calculations needed to be done, the longer it takes to process the data. Since molecular dynamics can involve hundreds of constituent atoms each with their own physical properties, we can expect the computation time take quite a while.

Even though the result of these simulations is a video lasting several seconds or a few minutes, the time it takes to process and produce them actually takes a long time – there are cases when it takes days to calculate all the necessary parameters, and sometimes even days! Supercomputers have thus been designed for the sole purpose of doing molecular dynamics – the IBM Blue Gene, for example, was made to study protein folding. The techniques used in protein folding research using IBM Blue Gene cascaded into other fields and applications that in the end improved our computer technologies.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Blue_Gene#/media/File:IBM_Blue_Gene_P_supercomputer.jpg

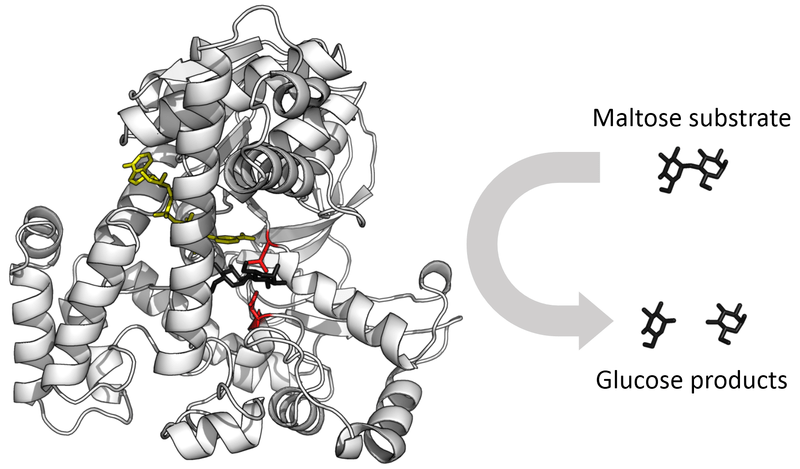

It gets even hairier when we think of simulating reactions such as enzyme catalysis and DNA transcription. Not only do we have a mix of various chemical species physically interacting with one another, but now we also have to model how they change each other chemically – how they displace constituent atoms from their molecules, or how they change the geometry.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glucosidase_enzyme.png

The solution to the problem of computational time is to sort of approximate the structure of the chemical species in the reaction. Researchers also omit other factors such as the detailed structure of large molecules. This method is called coarse-graining, wherein the “resolution” of the molecules is lowered, and meanwhile only the bulk effects of certain portions of the molecular structure is considered. The computational processing time is significantly lowered by orders of magnitude through this method. But in exchange, it becomes less accurate as we perform approximations.

Simulating biochemical reactions is especially useful today. Molecular biophysicists use computers to identify compounds that could disrupt the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 proteins, potentially finding a good treatment. It can also aide with finding out how mutations could possibly occur by finding transcription errors in computer simulations. But doing that requires processors from supercomputers already.

Whole Cell

Individual cells themselves are built up of countless biochemical reactions – which as we know now require expensive computational power. Simulating even a single cell now seems impossible. But with coarse-graining, simulating a single cell – with all its biochemical processes such as metabolism – becomes a reality.

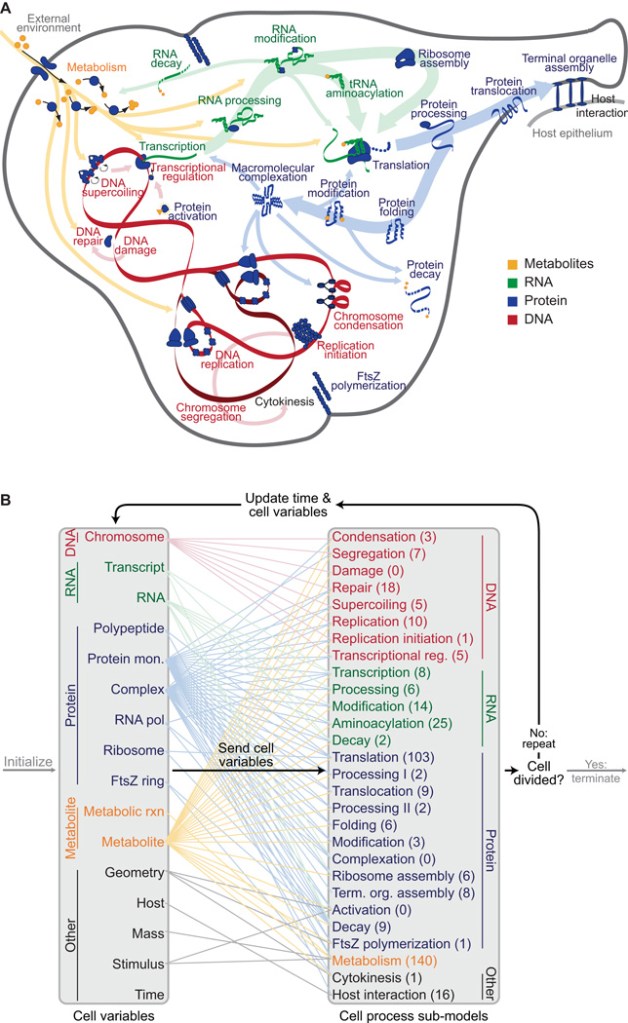

In 2012, Jonathan R. Karr and his colleagues from Stanford, along with scientists from the J. Craig Venter Institute, made a landmark study in biological simulations. In it, they applied what they called a whole-cell computational model to simulate an entire bacterium organisms. Specifically, they were able to simulate the a single Mycoplasma genitalium cell – a pathogen that is transmitted sexually.

They chose this bacteria species specifically because of its extremely small genome – it only contained 525 genes. This meant that it would be easier to identify the individual mechanisms that support it. Based on this genetic sequence only, they were able to predict how the bacterial cell would behave, how it would produce specific compounds, and how it would reproduce.

Using data from 900 different articles and books, they were able to reconstruct the M. genitalium genome with its physical and chemical properties. Each gene was grouped into 28 different cellular processes in which they played a role by producing enzymes and other proteins. These processes involved various biochemical reactions in which these enzymes played a role.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22817898/#&gid=article-figures&pid=figure-1-uid-0

Initially, they simulated each cellular process individually, refining it further. Afterwards, they integrated each cellular process into a single system by determining how their reactants, products, and side products affect each other.

By grouping all the processes together, they were able to simulate the behavior of the entire cell with its individual molecular components solely from this data – from DNA binding protein interactions, as well as metabolism as a cell cycle regulator (the cell cycle is generally the life cycle of the cell that involves reproduction, i.e. cellular division).

They were able to predict how these mechanisms would unfold in detail, thus providing new insight on how to hack them – since Mycoplasma genitalium is a sexually transmitted pathogen, disrupting these processes would be useful for preventing from multiplying and causing disease.

But, as mentioned, the Karr and his colleagues did a form of coarse-graining. Despite simulating the cell down to the molecular level, they did it on a time step of exactly 1 second – as in, they performed it in real time. They did not do a “slow-mo” version of a nanosecond to microsecond event. So there was no protein folding, motion, or geometric reconfiguration of the molecules – instead they only considered the bulk effect, focusing on the input of the cellular process and the output of the cellular process.

Still, what was amazing about this study was their ability to include the molecular components – something that was not previously done. This was by far the best simulation that built a cell from bottom up: based on the genotype (gene sequence) of the bacteria, they were able to predict the characteristics of the organism.

Whole cell modeling, Karr and is colleagues say in their seminal paper, can also be applied to recreating more complex cells such as human cells. This can have profound implications for understanding the dynamics of mutagenic diseases and cancer.

Whole Cell Molecular Dynamics?

As much as possible we would want to avoid coarse-graining if we are to fully simulate the cell down to the molecular level. Molecular dynamics often neglects the presence of other environmental factors other than temperature, while whole cell modeling does not capture the full resolution of what really happens.

There was, in fact, an attempt in 2015 by Feig and his colleagues to bridge this gap. They were able to recreate a whole-cell model for M. genitalium based on genotype just like Karr – the difference was that he started his model with the laws of physics, something done only in molecular dynamics. They included the motion of the proteins and DNA complete with their geometric structure. (You can view the diagrams here.)

It was amazingly complete with all the electrostatic interactions, transport of certain chemical species, and the networks of biochemical reactions all confined within the space of the M. genitalium cytoplasm. It even predicted molecular structures from the gene sequence only.

One can imagine how computationally expensive this was – indeed, they used a large set of powerful supercomputers at the RIKEN Integrated Cluster of Clusters in Japan. One can only imagine how long it took to process such a large amount of data.*

The simulation was also complete with the cellular processes and biochemical reactions present in Karr’s whole cell model. However, as Feig et al. emphasizes, their simulation remained highly speculative due to uncertainties in the complete geometric structure of the M. genitalium genome.

Regardless, this provides a stepping stone for a complete, fully detailed simulation of a general cell. This was a proof of concept that showed a whole cell molecular dynamics simulation was possible. As we continue to understand the cell in its full function and its full resolution , we’d be able to capture in detail the biological processes that drive life.

*I’d admit, I can’t find any sources on how long their computations took

References

Feig M, Harada R, Mori T, Yu I, Takahashi K, Sugita Y. 2015. Complete Atomistic Model of a Bacterial Cytoplasm for Integrating Physics, Biochemistry, and Systems Biology. J Mol Graph Model 58:1-9.

Groenhof G. 2013. Introduction to QM/MM Simulations. In: Monticelli L, Salonen E, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 43-66.

Karr JR, Sanghvi JC, Macklin DN, Gutschow MV, Jacobs JM, Bolival Jr. B, Assad-Garcia N, Glass JI, Covert MW. 2012. A Whole-Cell Computational Model Predicts Phenotype from Genotype. Cell 150(2): 389-401.

Wang JM. 2020. Fast Identification of Possible Drug Treatment of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) Through Computational Drug Repurposing Study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60(6): 3277-3286.