If you haven’t read Part 1, please read it here.

Planes and Spaces

Anyone who has taken a class from the levels of algebra to vector calculus would be familiar with the concept of the 2D xy-plane or the 3D xyz-space. A point on the xy-plane would be represented as (x,y) where x,y ∈ R. The xy-plane is often denoted as R2 = {(x,y) | x,y ∈ R}. The “2” exponent indicates that it has 2 dimensions and not an exponent.

The notation for 3D space is similar, represented as R3 = {(x,y,z) | x,y,z ∈ R}. We can actually extend this notation for any n-dimensional space as Rn = {(x1, x2,…,xn) | x1, x2,…,xn ∈ R}.

We are now presented with a question: how many points are there in the xy-plane, xyz-space, and further on? In other words, what is the cardinality of R2, R3, …, Rn? Finding this out requires some formal topology, so we will use some intuition.

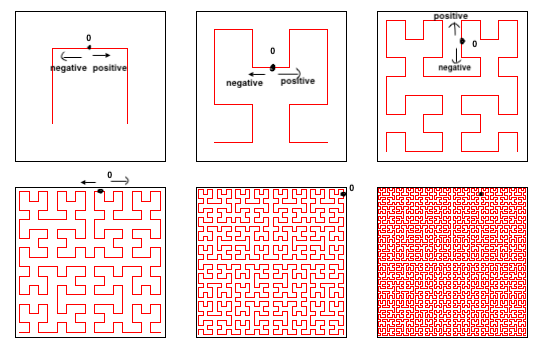

We can actually draw a line throughout the plane that goes on and on, without breaking or stopping. We can assign a point on this line the number 0. Every point before that will be assigned a negative real number, and every point after will be assigned a positive real number.

Edited from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hilbert_curve.png

While we only focused on a Hilbert curve covering a finite space, this can actually go on indefinitely throughout the entire xy-plane. This space-filling curve is called a Hilbert curve, and often comes in handy when assigning a specific point on a plane with a real number. And since we can assign every point with a real number, there is thus a direct correspondence between them, or a bijection. Therefore, the set of points on the plane has the same cardinality as the set of real numbers, or |R| = |R2| = 2ℵ0.

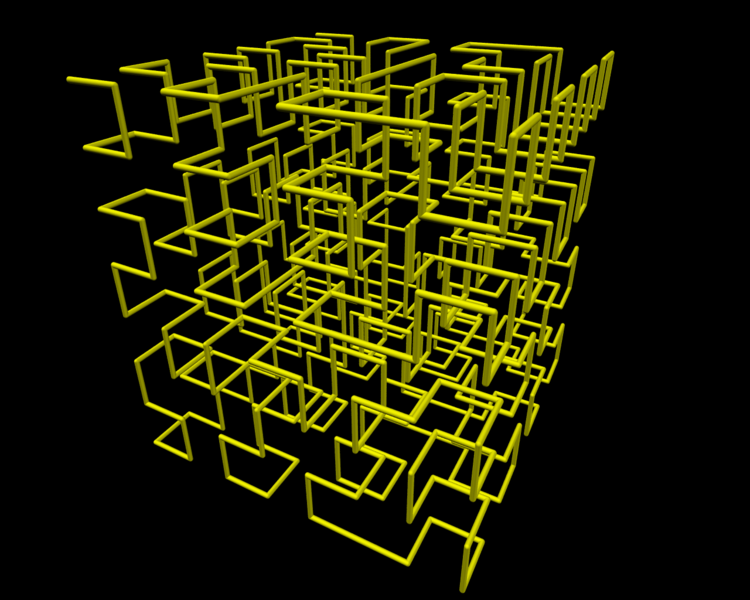

We can do the same for R3, proving |R3| = |R2| = |R| = 2ℵ0.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hilbert_curve_3D_2nd_iteration.png

We can even extend the notion of a Hilbert curve to n-dimensional spaces, thus proving that for any natural number n, |Rn| = |R| = 2ℵ0.

Complex Numbers

In high school, we’re told that √-1 has no solution. Today we know that’s not the case, since we defined √-1 = i, opening up a new set of numbers called the imaginary numbers. The rest of the imaginary numbers are just multiplies of √-1: we multiply any real number with √-1, writing it as bi where b ∈ R.

If we add an imaginary number to a real number a, it yields what we call a complex number, which we will call z. We can express z as z = a + bi. The set of complex numbers z = a + bi is also written as C such that C = {a + bi | a,b ∈}. If we multiply z with another complex number such as w = c + di, then zw = (a + bi)(c + di) = ac + (ad+bc)i + (bi)(di). Since i = √-1, i2 = -1. So, zw = ac – bd + (ad + bc)i.

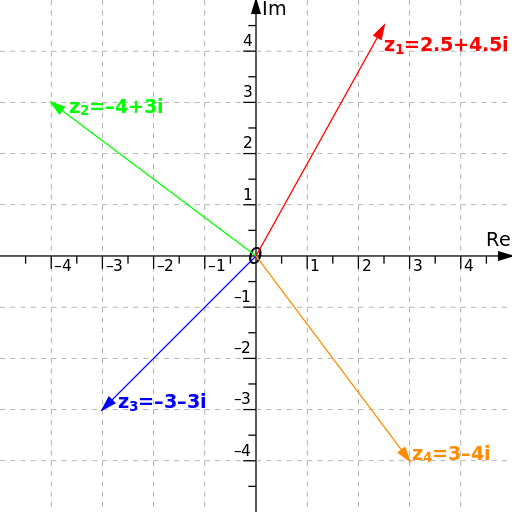

We can see that the set of complex numbers contains the set of real numbers. We can make a complex number have no imaginary component by setting b = 0, allowing i to disappear. Often, the set of complex numbers is represented as a plane.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Complex_plane_examples_1.svg

The main takeaway from here is that any complex number can also be represented as z = (a,b), with a being the real component and b being the imaginary component that is to be multiplied to i. It does not change anything other than the way we represent the complex number. Thus, the set of complex numbers can be expressed as C = {(a,b) | a,b ∈ R}. So if we multiply z = (a,b) with w = (c,d), then zw = (a,b) (c,d) = (ac-bd, ad+ bc). In away, complex numbers are “two-dimensional numbers”.

We can now clearly see that there is a direct correspondence that is bijective between C and R2, and the only difference between the two sets is that you can multiply a point in C with another point in C. This being the case tells us that C has the same cardinality as R2, thus |C| = |R2| = |R| = 2ℵ0.

Beyond

There are actually more numbers beyond the complex numbers. By thinking of complex numbers as two-dimensional numbers, mathematicians have also invented four-dimensional numbers called quaternions, and even eight-dimensional numbers called octonions, and it goes on and on. So far, is are no such thing as a three-dimensional number, or anything in between four and eight, because of the sole reason that it’s hard to craft rules for them.

Those numbers are called hypercomplex numbers. Quaternions would correspond with points in R4 and octonions with points in R8. Since we’ve already established that |Rn| = |R|, we can say that the cardinality of quaternions, octonions, and so on is also 2ℵ0.

So how many numbers are there? There are 2ℵ0 numbers.

References

Rudin W. 1976. Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc. 342 p.

One thought on “How many numbers are there? (Part 2)”