Natural Numbers – A.K.A. Counting Numbers

Let’s begin with the counting numbers that we were familiar with since preschool. One, two, three, four, five… and so on. We would ask, “what’s the biggest number?”. Someone might have lied to us that it was 100. Obviously, it isn’t – there’s still 101, 102, 103,… and it keeps going.

If we think of any counting number, be it one million, one billion, or the largest counting number we could even type on a word document, there’s always another counting number after that. Just add + 1. So in short, there is no end to the counting numbers. But mathematicians are creative – while we cannot find the largest counting number, they indeed have an answer to the question, how many numbers are there?

And the answer: aleph null, written as ℵ0.

“Wait, what? Is that even a thing?”

Well, according to the current rules we follow in mathematics, this is true. While claiming that the answer is infinity is still correct, this interpretation is more precise since ℵ0 is a type of infinity. As we’ll see in the next sections, there are actually bigger infinities.

In more formal terms, ℵ0 is the cardinality of the set of natural or counting numbers. The cardinality of a set just tells us how many members there are in a mathematical set. For example, the A = {a,b,c,d,e,f} has cardinality |A| = 6.

For numbers, it’s the same. The set S3 = {0,1,2,3} would correspond with |S3| = 4, S4 = {0,1,2,3,4} with |S4| = 5, and set S10 = {0,1,2,…,10} with |S10| = 11. In general, if i is a counting number such that all Sk = {0,1, 2,…, k}, then |Sk| = k + 1.

If we allow i to go on until infinity, eventually we’ll include all counting numbers. Hence, Si would actually be the set of all natural numbers, which we usually call N. Thus, we write aleph null in an equation as |N| = ℵ0..

The concept of aleph null was first crafted in 1874 by the German mathematician Georg Cantor, who is credited as the “father of set theory”. Despite being renowned today, Cantor experienced harsh criticism and backlash from his colleagues due to this extremely counter-intuitive concept. It took years before he was duly credited with his ideas, where in 1904 the Royal Society awarded him with the Sylvester Medal to honor his work.

The Integers

The set of integers Z is the set of natural numbers combined with the negative numbers. This means that Z = {…,-2, -1, 0, 1, 2, … }. We have established that there are ℵ0 natural numbers. What about the integers? That is, what happens if we include the negative numbers?

Let’s work on a conjecture: the number of integers equals that of the number of natural numbers. Here’s the proof.

Suppose we have a function f that maps a natural number n to the integers defined as follows

In other words, if n is even, then the functional value is positive. On the other hand, if n is odd, then the functional value is negative. Judging from the values that the function spits out, we can see that for every natural number, there is a corresponding integer and vice versa. In mathematics, we call this a bijective function. And it is easy to believe that if this is the case, then the number of integers is the same as the number of natural numbers. Therefore, there are also ℵ0 integers.

Since there are ℵ0 integers, we can state this as |Z| = |N|. There is a technical term for sets that have the same cardinality as the natural numbers – they are said to be countable sets. It makes sense, since for every member of the set there is a corresponding counting number assigned to it.

The Rational Numbers

The set of rational numbers Q is the set of integers combined with the set of fractions and their negative counterparts. It would be hard to write it down as a list, so we instead we express it as Q = {a/b | a,b ∈ Z}. (| is read as “such that”, ∈ is read as “an element of”).

So how many rational numbers are there? The answer is also ℵ0.

The proof, which was cooked up by Georg Cantor himself, is as strange as the concept of ℵ0 itself. It goes by organizing all the rational numbers into a table: each row represents a numerator, and each column represents the denominator that will divide it.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diagonal_argument.svg

In effect, we can draw an arrow snaking through each table entry indefinitely, as shown above. The first table entry it hits will be assigned the number 1, then the second the number 2, the third number 3, and so on. We can interpret this as being able to count the rational numbers. So now, we can observe that for every positive rational number, there is a corresponding natural number as it goes on indefinitely.

If we include the negative rational numbers, then we’ll assign them the negative counting numbers such as -1, -2,… Since we’ve already proven that the integers have the same cardinality as the natural numbers, we can therefore say that the cardinality of rational numbers is also ℵ0.

So far, we have proved that the set of rational numbers is also countable since it has the same cardinality as the set of natural numbers. If we were to write an equality representing the cardinality of the set of rational numbers Q, then it would be stated as |Q| = |N| = ℵ0. We can already see that |Q| = |Z| as well from the previous section.

The Real Numbers

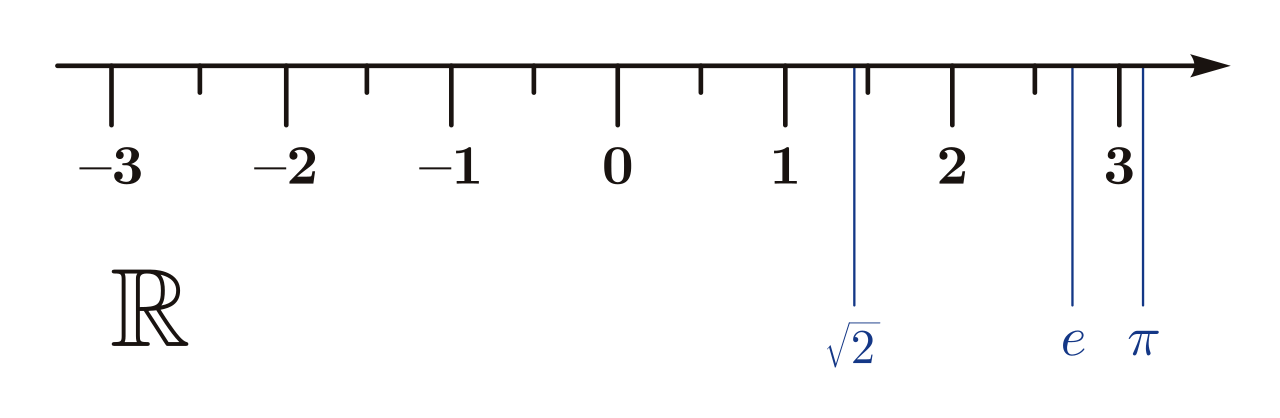

The set of integers contain the set of natural numbers, and the set of rational numbers contain the set of integers. Similarly, the set of real numbers contain the set of rational numbers, plus some additional elements called the irrational numbers. This includes the numbers π, e, √2, and numbers with never ending decimals that do not have a predictable pattern, such as 5.123899817283197… The set of real is usually represented as R.

Do the real numbers have the same cardinality as the natural numbers – that is, are they countable? The answer to this requires a rather formal proof, so this will require a lot of focus.

We allow a set A to be a countable set (|A| = |N|) containing never ending decimals with no predictable pattern. We list them down on the table below:

| 1 | 1.7219804378291740192… |

| 2 | 2.1245156325342523454… |

| 3 | 7.1239190283901293810… |

| 4 | 6.1231262812934810294… |

| 5 | 0.1239809182371827381… |

| 6 | 4.1273891273891239801… |

| 7 | 0.6127836816278317816… |

| 8 | 5.1329815012903813191… |

| 9 | 3.6294038502858290385… |

| 10 | 9.1239081293081391238… |

For every nth number (assigned in the left column), the nth digit is colored red (with the number before the decimal being the first digit). We can write a number whose nth digit always differs from the nth digit from the nth number: 2.235094767… This means that this number differs from each member of A by at least one digit – therefore, this number does not belong to A.

Since we can replace the elements of A with any other decimal, this proves that every countable subset A of R is a proper subset – meaning, that there’s a number in R that’s not in A. This is subtle, but very crucial.

This implies that if R was countable, then it would also be a proper subset – meaning that there’s a number in R that’s also not in R, which does not make any sense. Thus, the set of real numbers R is uncountable.

So what does this tell us? Since the set of real numbers is uncountable, it follows that its cardinality is not the same as the set of natural numbers, ultimately meaning that the cardinality of R is not equal to ℵ0. We write this as |R| ≠ ℵ0.

This begs the question – how do we represent |R|?

Intervals

We can think of a subset J of R of all the numbers between 0 and 1. We can prove that |J| = |R| by thinking of a function that assigns every real number with a number between 0 and 1, just like how we proved that |Z| = |N|. Any function that does the job will do, but the simplest one is presented below

With x being a real number. So since we can assign all real numbers with a specific number between 0 and 1, we can say that |J| = |R|. This result will prove useful in the next section.

The Power of Power Sets

Let H be a subset of natural numbers, say G = {1,2} so |G| = 2. Then its power set of G, P(G), is the set of subsets of G. We can actually list down the power set’s elements: P(G) = {{},{1},{2},{1,2}}. We write the empty set, which is the set that does not contain any elements at all, as { }.

We can notice that the cardinality of P(G) is |P(G)| = 4 = 2|G| = 22. If we choose another set H = {1,2,3} with |H| = 3, then P(H) = {{},{1},{2},{3},{1,2},{1,3},{2,3},{1,2,3}}. So, |P(H)| = 8 = 23 = 2|H|. This trend actually continues for any set. So we can actually say that any set X, the cardinality of its power set P(X) is |P(X)| = 2|X|.

So what if we consider the power set of the natural numbers P(N), such that |P(N)| = 2|N| = 2ℵ0? It will be hard to list them down, but it would look something like {{},{0},{1},{2},….,{0,1},{0,2},…,{1,1},{1,2},…{1,2,…}}. Now here comes another crucial part, in which understanding it will require a lot of focus again.

We can think of a number between 0 and 1 whose decimal digits have the same order as a subset of N, which is always a member of P(N). Examples are shown below.

| {1,2,3,4,5,6,7} | 0.1234567 |

| {2,3,4,5,6,7,8} | 0.2345678 |

| {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,…} | 0.1234567… |

| {5,6,7,8,9} | 0.56789 |

| {11,12,13,14,15} | 0.1112131415 |

| {11,12,13} | 0.111213 |

| {3,4,5,6,7,8,…} | 0.345678… |

| {0,1,2,3,4,5} | 0.12345 |

| {0,1,2} | 0.12 |

| {8,9,10,11} | 0.891011 |

Since we can assign a number between 0 and 1 with a corresponding member of P(N), that is, a subset of N. Thus, since in the previous section J represents the numbers between 0 and 1, |P(N)| = |J| = |R|. Thus, |P(N)| = 2ℵ0 = |R|.

We find that the cardinality of the real numbers is 2ℵ0, which is obviously bigger than ℵ0. This goes to show that there are infinites bigger than other infinites. We can actually stop here and say that there are 2ℵ0 numbers, since the real numbers are the only ones we use in measuring things such as length, mass, time, etc. But we can actually go even further.

NEXT ARTICLE: Part 2

References

MathOnline [Internet]. c2019. Torun, PL: Wikidot [cited 2020 June 25]. Available from: http://mathonline.wikidot.com/the-set-of-all-subsets-of-natural-numbers-is-uncountable.

Rudin W. 1976. Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc. 342 p.

One thought on “How many numbers are there? (Part 1)”