A simple assembly of atoms: two hydrogens, one oxygen. Its formal chemical name is dihydrogen monoxide (H2O), but of course we never call it that — we call it water.

Despite being so simple, it’s amazing to see how water’s simple structure and arrangement of atoms have led to consequences such as weather, climate, habitable planets, and eventually, life. Here we explore how this molecule has been profound in almost every aspect in science, and even in the understanding of human civilization.

Perfect Properties

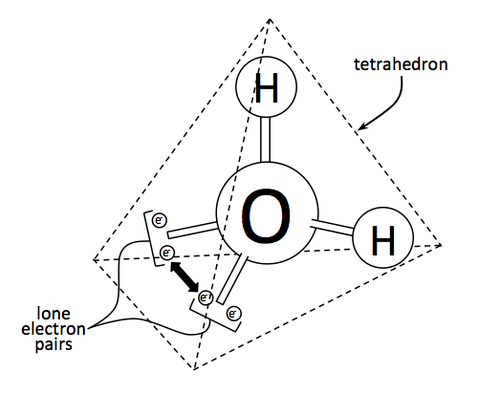

Edited from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tetrahedral_Structure_of_Water.png

| Molecular Formula | H2O |

| Molecular Weight | 18.015/gmol |

| Boiling Point | 100 °C |

| Melting Point | 0 °C |

| Color | Colorless |

| Miscibility | Completely miscible |

| Density | 1.00 g/cm3 |

| Dynamic viscosity | 0.8949 cP at 25 °C |

| Heat of Vaporization | 9.717 kcal/mol |

| Surface Tension | 71.97 dyne/cm at 25 °C |

| Index of Refraction | 1.333 |

The geometry of a water molecule is actually a tetrahedron, with two hydrogen atoms poking out like the handles of a bicycle, and two lone pairs of electrons in similar arrangement. Here, it is clear how oxygen tends to grab the electrons more, especially since hydrogen still manages to give up its single electron for covalent bonding. Oxygen is said to be more electronegative than hydrogen.

Since the electrons tend to condense around the oxygen atom more, that side has a more negative partial charge. This imbalance of charge results in what is called polarity. This polarity allows the water molecule to electrostatically interact more with other molecules with polarity, both water and those other than water. Thus, water can freely mix with other similar substances: like dissolves like.

But when water molecules interact with each other, the attractive force known as hydrogen bonding is so intense that separating them requires a lot of energy. That’s why drinking even just a quarter of a liter brings a feeling of coolness, and also why bathing seems to dispel the summer warmth – water absorbs so much heat. Thermodynamically speaking, they have a high heat capacity.

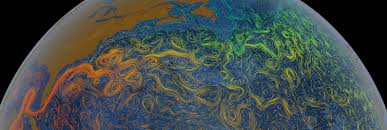

Its effects can be seen at a planetary scale. Ocean currents dissipate heat throughout the globe, creating more tolerable climates both at the warmer areas of the world and in the colder. Europe would be a cold wasteland if it weren’t for the Atlantic currents such as the Gulf Stream.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gulf_Stream_Sea_Surface_Currents_and_Temperatures_NASA_SVS.jpg

In its liquid and gas state, water is used as a reference model for fluid mechanics, being the substance that’s practically everywhere on the surface of the Earth.

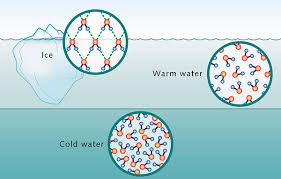

Its geometry also has effects on how it transitions from one phase of matter to the other. At room temperature (298 K or 25 deg C), scientists often set water’s density to 1.00 g/cm3 (as per Table 1), hence being the reference value for all densities of substances. This is because it’s so abundant – even the air carries water vapor. But at lower temperatures, things start to get weird: water’s density continues to increase as it is cooled, until it reaches 4 deg C – where it reaches its maximum density. Colder than that, it starts to arrange itself into ice – which, because of its crystal structure, creates spaces in between molecules that result into lower mass per volume. This actually explains why icebergs float, and why its liquid states exist below the surface of frozen lakes, ponds, and rivers.

Source: http://ponce.sdsu.edu/properties_of_water.html

Origins of Water

Earth is in the Goldilocks zone of the Solar system – an area around a star (in this case the Sun) that’s not too hot for water to evaporate and not too cold for water to freeze over. Its conditions allow for mostly liquid water to thrive, with some areas that are frozen, serving as a reservoir.

There are actually two theories on the origin of water: one is that they came from external sources such as comets (which are basically dirty snowballs in space), and the other is that they were outgassed from the depths of the primordial Earth via volcanic eruptions.

If the external source theory were true, then the ratios of hydrogen isotopes on modern day comets and our oceans would be the same. Hydrogen, being an integral component of water, can come in the form of protium (one proton, one electron), deuterium (one proton, one electron, one neutron), and tritium (one proton, one electron, two neutrons). When geologists measured the ratio of deuterium to protium on the comets Halley, Hyutake, Hale-Bopp, and 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, they found that it was twice that of Earth’s waters. Thus, the external source theory is implausible.

The volcanic outgassing theory, then, is more plausible. Today, volcanoes do expel roughly the same gases as those outgassed in Earth’s early history, but not on the same scale. The intense heat and fluid-like motions of the mantle billions of years ago would have resulted in a massive escape of gases dissolved in the molten liquid, water vapor included. As the Earth cooled, the water would condense and then form our seas and oceans.

Source: http://resilience.earth.lsa.umich.edu/Inquiries/Inquiries_by_Unit/Unit_8.htm

The formation of vast swaths of liquid water on Earth would prove essential for the development of the lush world we know today. The surface of the globe today is 75% water. Compared to planets like Mars or moons like Europa – which both have water mostly in the form of ice – our world’s oceans harbor an uncountable number of living things. This is all because water serves as a perfect medium for the development of complex objects such as life.

Birth of Life

The life-giving properties of water is not an exaggeration: it serves as a medium that carries and circulates polar biomolecules and minerals throughout the body. This same circulation of water also regulates the organism’s internal temperature, allowing life to function at usually 37 deg C, where most biological compounds are at its most functional and active. But other than being a medium for life, it’s also possibly the reason why life began in the first place.

Many people often wonder how such a complex system such as life emerged. Some even claim that this seemingly high order of organization violates the second law of thermodynamics, which roughly states that the disorder of an isolated system must always increase. That can be partially explained by arguing that living things are open systems and not isolated ones since they regularly excrete waste and take in energy. While this is true, it’s not the full picture. Actually, the very biomolecules of life – proteins, DNA, phospholipids – can increase the system’s entropy as they organize. We just need to add water.

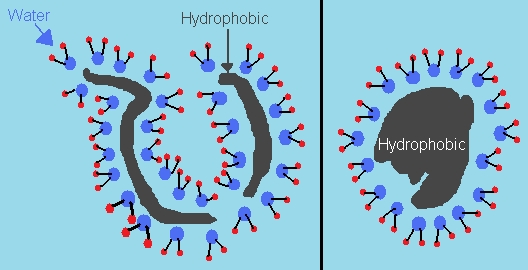

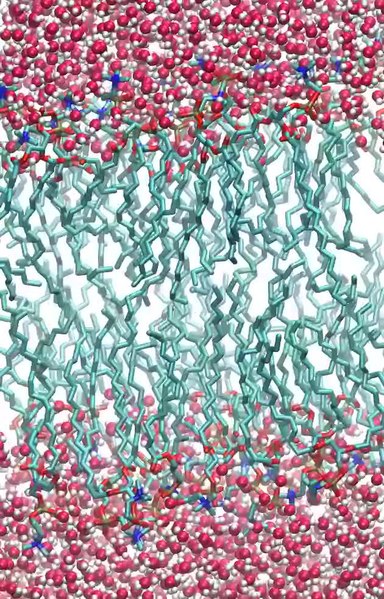

The long string of amino acids known as proteins have certain portions that are hydrophobic – or water-hating – and regions that are hydrophilic – or water-loving. In other words, one side repels water molecules, and the other attracts them. Alone, proteins cannot fold since certain regions attract and repel each other, thus preventing it from conforming to an ordered geometry. But the presence of water sort of forces them to do so without violating any physical laws.

When water molecules are exposed to the hydrophobic portions of the protein, they tend to arrange themselves since their movement is restricted. Thus, the entropy of these molecules decrease. But when they are exposed to the hydrophilic portions, their interactions allow them to move freely, as if it was business as usual since the polarity of the hydrophilic portions resemble that of water. Thus, the entropy increases. In fact, this increase overrides the decrease in entropy when the protein starts rearranging itself. In other words, the net entropy increases.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Water_Entropy.png

The process and explanation is the same with DNA molecules when they fold. It also happens with plasma membranes which are composed of phospholipid molecules with hydrophobic lipid tails and hydrophilic phosphate heads. Tucking the hydrophobic tails away from the water to allow the surrounding molecules to move freely. The phospholipid molecules then array themselves to create a sheet, forming a barrier against the water medium.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Molecular_Dynamics_Simulation_of_DPPC_Lipid_Bilayer.webm

As these biomolecules are able to assemble into complex structures in the presence of water, some of their forms tend to be sturdier in the presence of external factors such as ultraviolet radiation, oxidative chemicals, and reductive chemicals. Those biomolecule forms thus survive more, allowing them to mutate to even sturdier forms that are more complex. Eventually, these molecules aggregate with each other to give birth to living things.

It’s then no wonder why humid and tropical places such as the Amazon and the Coral Triangle harbor such intense biodiversity. Life relies on water so much that the beginning of our societies rests on the presence of fresh water around lakes and rivers.

We Go Where Water Goes

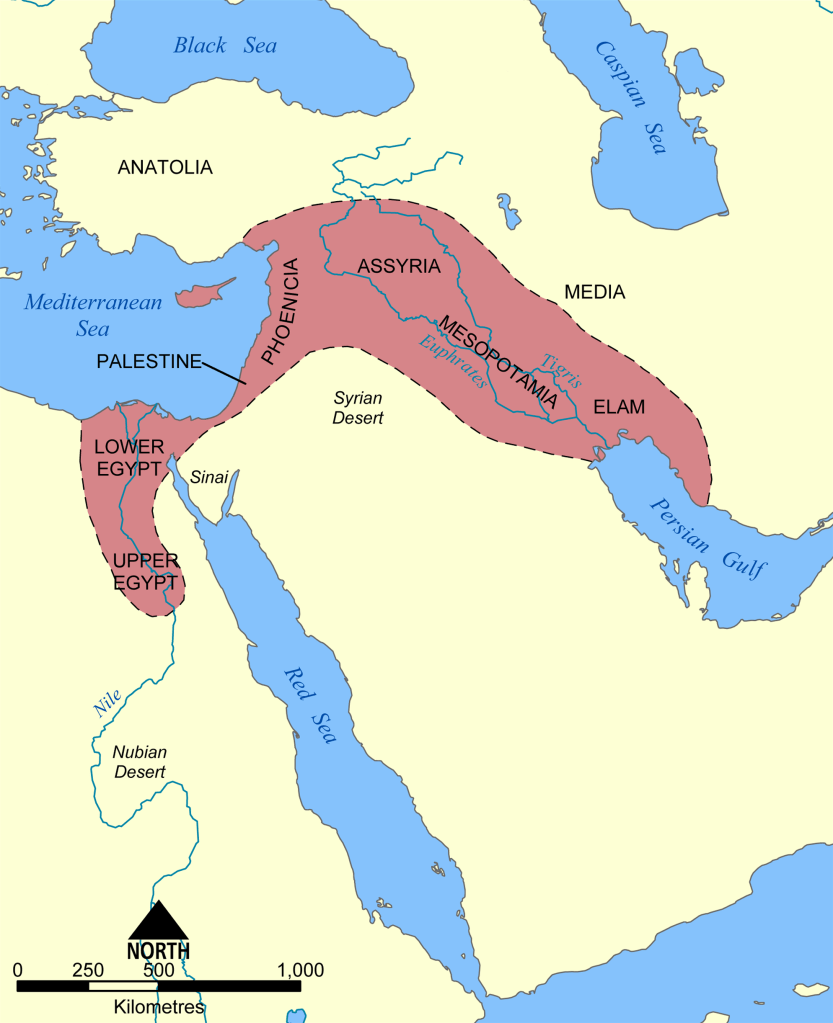

Even in the driests of deserts, if a river flows, a small sliver of land would become wet and fertilized with the minerals that come with the flowing water. We humans would then cluster around these rivers, first to build agricultural communities on the fertile land. As population grows due to the abundance of food, villages, towns, cities, and eventually empires appear. The first foundation of civilization was the presence of water.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fertile_Crescent_map.png

The Indus River provided the ancient Indians with an oasis in the midst of dry land. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers formed a fertile crescent in the middle of a desert, allowing the Babylonian and Sumerian Empires to form, establishing sophisticated cities in the Middle East. The Yellow River in continental East Asia allowed the Chinese Empire to grow. The Nile River gave sustenance to the Egyptians who would build the Sphinx and the Pyramids.

Even in modern society, the presence of clean water can be a determinant of how developed the area is – either it is underdeveloped, or its rapid industrialization has led to sewage problems. And this is of course still an issue, as places such as rural Africa lack filtered water. Meanwhile, dense urban cities such as those in the United States, India, and China have challenges with water pollution, and authorities are looking for new innovations in order to solve this.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_pollution_in_India#/media/File:Oshiwara_river.JPG

As we humans look for planets to expand to, we actively search for ones that harbor water, preferably liquid water. That’s why astronomers are always excited to find worlds in the Goldilocks zone. While we have found worlds like that – some even with liquid water – we still cannot determine if its conditions for habitability suit humans.

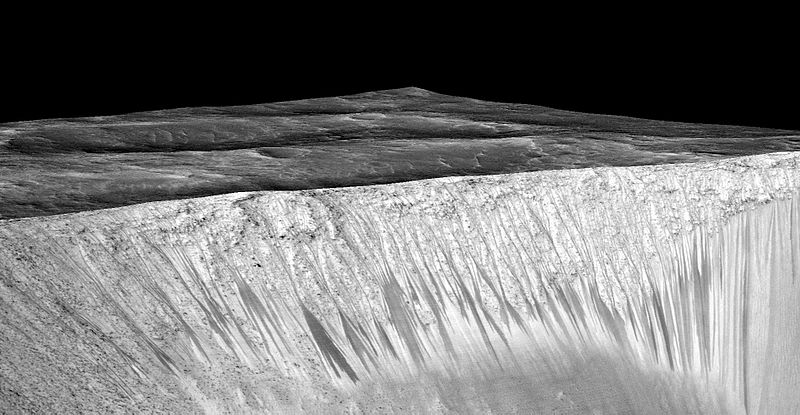

Our strongest candidates today in our Solar system remain to be Mars and the Galilean moon of Europa, despite not being in the Goldilocks zone. Astrobiologists are also speculating that certain conditions such as underground volcanic activity could warm subterranean lake chambers or underground oceans, providing conditions for life to develop.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Liquid_water_on_mars.jpg

Water is ubiquitous – and while many of those with proper access to clean water take it for granted, its presence has driven the development of both life and society. Its simple geometry and composition has had far reaching consequences, and if it were different, we probably would not even exist. The next time you run a tap to wash your hands or brush your teeth, think of how this magical substance has led to where human civilization is now.

References

Khan MY. 1985. On the Importance of Entropy to Living Systems. Biochemical Education 13(2): 68-69.

PubChem [Internet]. c2020. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information [cited 2020 June 22]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Water

SEASHarvard [Internet]. c2020. Cambrdige, MA: Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences [cited 2020 June 22]. Available from: https://courses.seas.harvard.edu/climate/eli/Courses/EPS281r/Sources/Origin-of-oceans/1-Wikipedia-Origin-of-water-on-Earth.pdf

Tarbuck EJ, Lutgens FK, Tasa D. 2012. Earth Science 13th Edition. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall. 740 p.

Urry LA, Cain ML, Minorsky PV, Wasserman SA, Reece JB. 2017. Campbell Biology 11th Edition. New York City (NY): Pearson Education. 1284 p.

One thought on “The Magic Liquid Called Water”