What is Biophysics?

Life has underlying physics behind it — and that’s a well known fact. After all, everything is physics. But most of the time, physics is concerned with objects almost totally unrelated to biology — things smaller than cells such as atoms and photons, or things bigger than biospheres such as galaxies and stars.

But there’s a field of study called biophysics. While not well represented in popular science media, biophysics is very much alive in terms of research. Understanding the physics of life is not very obvious due to its extreme complexity, but the recent decades have seen progress in connecting the concepts of energy and entropy to things like proteins and evolution.

We’ll quickly tour how physics is applied to biology, down from the level of molecules up to the level of populations. Brace yourselves, since we will quickly jump from one topic to the next.

A Macroscopic Understanding

Prior to the advent of sophisticated laboratory equipment which allowed us to peer into the submicroscopic world, the application of physics to biology was limited to the level of organs and cells.

Bones and muscles are responsible for generating forces and torques that result in displacement. This is generally well understood in the context of classical dynamics and statics. Despite relying on centuries-old theories, biomechanics — which is the field that studies these — is still very much alive in research today. How the bones and muscles are arranged, how they affect one another, and how they are stimulated by the nervous system is quite complex and thus often rely on computer simulations to understand them.

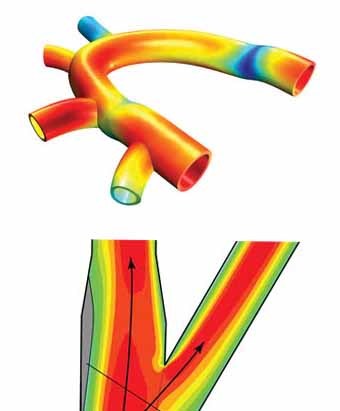

Figure 1. Left to right: (a) Blood flow modeling in blood vessels, (b) the forces in bones from De Motu Animalium by Giovanni Borelli.

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biomechanics#/media/File:Giovanni_Borelli_-_lim_joints_(De_Motu_Animalium).jpg, https://i1.wp.com/basicmechanicalengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/blood-flow.jpg

Biomechanics is also important in understanding blood flow through fluid mechanics, as well as studying how the gases found in the same blood diffuse across membranes. These models mostly work on the macroscopic level.

The physical understanding of life on this level plays an essential role in medical research. Developing prosthetics would require a solid foundation in biomechanics, as they would need to mimic the movement of the same bones and muscles. The fluid nature of blood is pertinent to the understanding of hypertension and blood clots. But a huge bulk of the physics research today in biology talks about objects smaller than even the cell.

Molecular Biophysics

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photo_51#/media/File:Photo_51_x-ray_diffraction_image.jpg

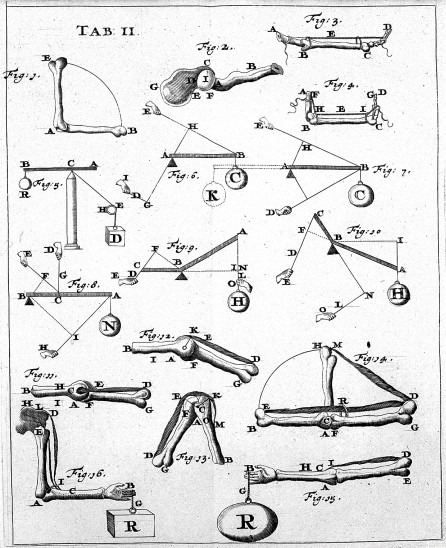

With the elucidation of the structure of DNA by Franklin, Watson, and Crick using X-ray crystallography, the physico-chemical nature of life was beginning to be more and more apparent. And in recent years, physicists, biologists, chemists, and even mathematicians have encountered a fundamental problem in one of the main molecules of life: proteins.

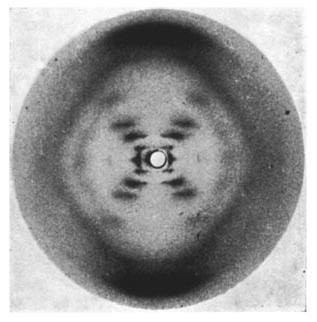

Proteins are an assembly of various units of amino acids, which themselves have different properties. Thus, when these amino acids are strung along together into a chain, some of the units attract each other, and others repel, allowing the chain to fold and crumple to conform to a specific geometry. This is called protein folding. Now, as simple as it may seem, it’s anything but that.

Many factors fall into obtaining the shape of a protein. For one, there are external factors. While temperature of the surrounding environment affects the energy of folding, the medium (usually water) also exerts intermolecular forces on the protein subunits which in turn affect the folding process. There are internal factors as well: the amino acid units themselves can repel and attract other amino acids units in the protein. One can only crunch a limited amount of data to obtain at least an approximate view of the resulting protein shape using computer simulations — which, by the way, takes a great deal of time to process.

Because of the presence of atomic interactions, some quantum mechanics computations are involved in the computation. But overall, most models of protein folding use statistical mechanics to study the relationships between the many particles involved in the system. In a statistical mechanical model, the properties of the many components involved are understood in terms of the probable energies and entropies – hence, statistical.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folding_funnel#/media/File:Folding_funnel_schematic.svg.

The concept of protein folding has profound implications in developing medicines, where certain proteins are drug targets which the pharmaceutical acts on. Protein misfolding is also relevant in neurodegenerative diseases, since misfolding leads to malfunction of certain biological processes. For further discussion, you may check out Reynaud’s article on Nature.

Molecular biophysics also involves the imaging and elucidation of the structure of various biomolecules including both proteins and DNA. Currently, techniques involved in such imaging are cryo-electron microscopy, X-ray crystallography, and optical tweezers.

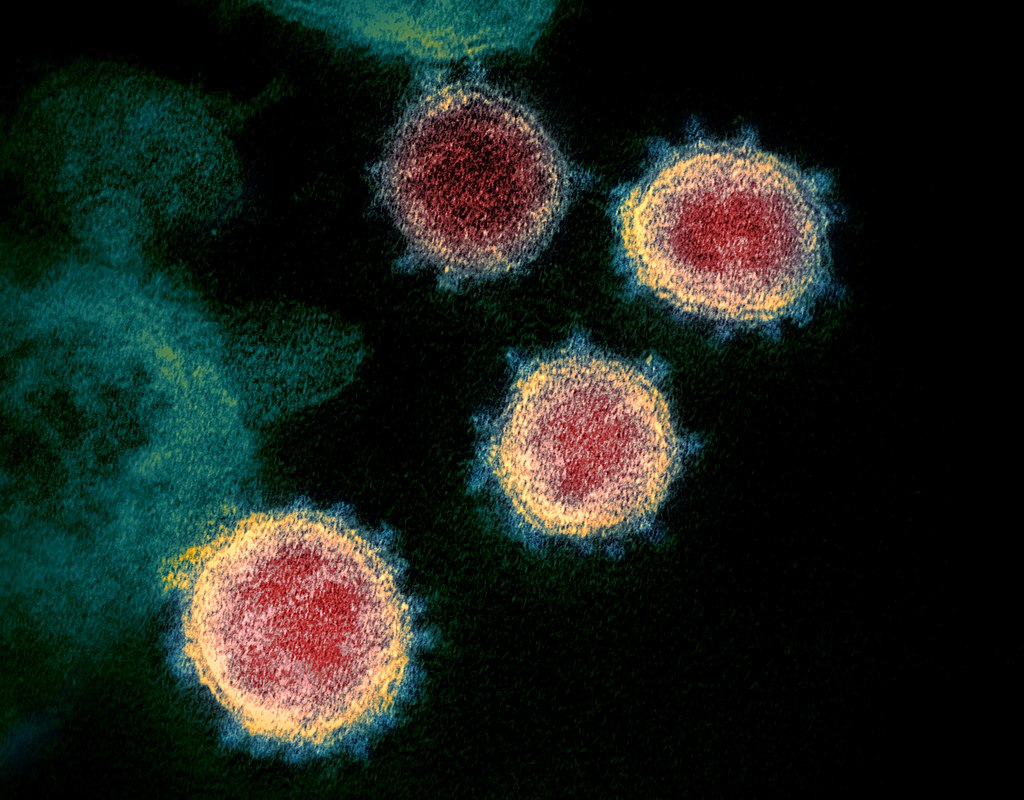

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Severe_acute_respiratory_syndrome_coronavirus_2#/media/File:Novel_Coronavirus_SARS-CoV-2.jpg.

This field of biophysics is especially important in relation to COVID-19 pandemic. Recognizing the structure of the spike proteins that coat the SARS-CoV-2 virus will aid in the invention of vaccines and drugs for treatment. However, this method of course applies to any kind of virus.

Now we can clearly see that biophysics integrates concepts from classical physics and modern physics. But the application of these principles is not always obvious when one considers higher levels of organization. At the level of proteins already, scientists stumble upon problems that are nonlinear. As one delves deep into the field of biophysics, a common theme could be observed: complexity.

Increasing Complexity

As complexity increases, certain minute details are intentionally left out. In a complex system, tracking the behavior of every component would be onerous.

Modeling the behavior of complex systems would rely on recognizing the pattern of their behavior. This contrasts with predicting phenomenon by deriving equations from a prescribed set of principles. Oftentimes when the patterns are recognized, a computer simulation would run to determine how the complex system changes.

Actually, a lot of research in biophysics involves modeling biological phenomena using an analogy from simpler physical phenomena, which can be described mathematically. This way, complexity of the system is somewhat simplified.

For example, birds in a flock might be viewed as similar to moving fluid particles. Or ants in a colony can be modelled as cellular automata, in which the level of order and disorder of movement can be understood in terms of entropy.

Figure 5. (a) Birds in a flock, (b) ants in a foraging trail

Sources: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wesselburen_flock_of_birds_04.03.2011_18-20-45.JPG, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Foraging_Ants_(223219187).jpeg

Clearly, the smaller details would not be relevant. How the neurons fire to recognize a path wouldn’t be important in determining the patterns of its work. The mechanism of the bird flapping its wings wouldn’t be crucial in recognizing flight direction patterns. Nor would the folding of the protein in SARS-CoV-2 be important in predicting how the COVID-19 would spread from location to location.

Understanding how life itself began is a matter of examining a complex system of interacting molecules. Since biomolecules such as proteins themselves are already complex, what more for the emergence of life?

Life Itself Emerges

One of the criteria for things to be considered life is that they reproduce. Other scientists might call this self-replication, because, well, they produce copies of themselves by themselves. Interestingly, this means that life begins as an order out of disorder. This sounds like it violates the second law of thermodynamics, which roughly states that the disorder of the universe must increase.

In 2013, Jeremy England published a paper that asserts that this is not the case. Actually, he proved mathematically that self-replication is bound to happen. Life would have begun as a set of molecules that was able to replicate itself. The molecule will often restructure itself to dissipate energy, hence following the second law of thermodynamics. And most of the time, that restructuring will reduce its chance of being degraded, thus becoming more abundant. This agrees with Darwin’s principle of natural selection.

Eventually, those molecules — nucleic acids such as RNA and DNA, and proteins — would assemble with each other to form cells and organelles, thus forming the first unicellular organisms. The rest is history after that.

England’s theory is yet to be proven, but its use of physical principles with its underlying mathematical rigor makes it hard to doubt. An experimental proof of this theory would make the physical understanding of life less elusive.

In conclusion, life is extremely complex, from the smallest protein that folds to the behaviors of populations of organisms. But biophysicists are challenged with breaking down this complexity in order to predict and understand its behavior. And while the challenge is difficult, the latter half of the 20th century and the recent years of the 21st have seen great strides. And with finding out how life began, we can finally connect the pieces in the physics of life.

References

Biophysics [Internet]. c2020. Rockville, MD: Biophysical Society [cited 16 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.biophysics.org/blog/coronavirus-structure-vaccine-and-therapy-development

England JL. 2013. Statistical physics of self-replication. J. Chem. Phys. 139(12): 1-8.

Evolution Berkeley [Internet]. c2008. Berkeley, CA: University of California Museum of Paleontology [cited 16 June 2020]. Available from: https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/evo_25.

Paluch EK. 2018. Biophysics across time and space. Nature Physics 14(7): 646-647.

Reynaud E. 2010. Protein Misfolding and Degenerative Diseases. Nature Education 3(9): 28.

Scott LR, Fernandez A. 2017. A Mathematical Approach to Protein Biophysics. Cham (ZG): Springer International Publishing. 290 p.

Urry LA, Cain ML, Minorsky PV, Wasserman SA, Reece JB. 2017. Campbell Biology 11th Edition. New York City (NY): Pearson Education. 1284 p.

One thought on “The Physics of Life: A Tour of Biophysics”