| Atomic Number | 1 |

| Atomic Weight | 1.00794 amu |

| Melting Point | 13.81 K |

| Boiling Point | 20.28 K |

| Phase at Room Temperature | Gas |

| Period Number | 1 |

| Group Number | 1 |

History

The term “hydrogen” is derived from the Greek words hydro and genes, together meaning “water forming”. The first to name it in its molecular gas form, H2, was Antoine Lavoisier in 1783. Although Robert Boyle in 1671 was the earliest known to record the production of a gas when iron filings and dilute acids are made to react, it was Henry Cavendish who identified it in 1766. Years later in 1781, he was able to recognize that burning the gas produces water.

Structure

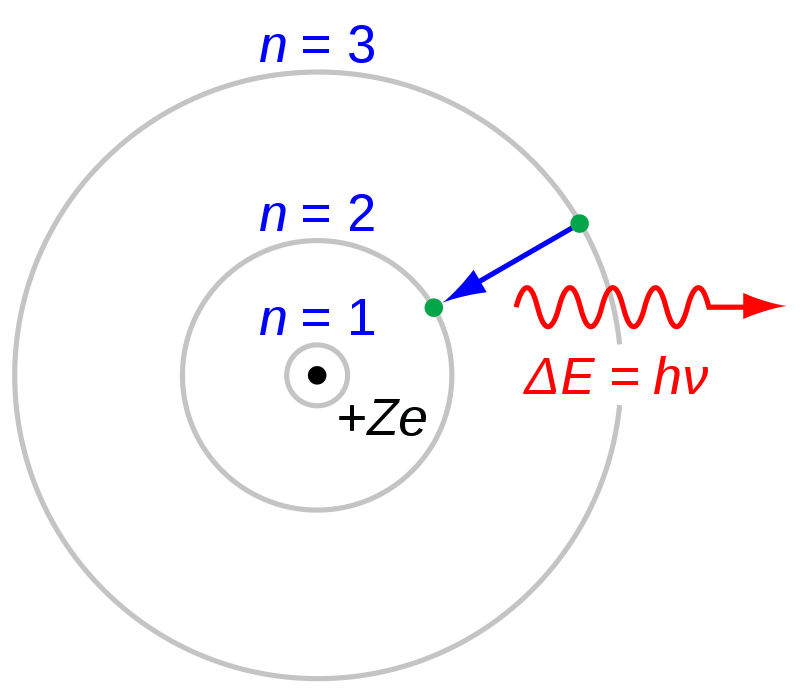

Hydrogen in its non-molecular form is by far the simplest element in terms of structure: it consists of one proton and one electron. The central region containing the proton is what we know as the nucleus. In the Bohr model, the electron orbits at specific distances determined by a discrete amount of energy it could have, known as “energy” levels. It is visualized below.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bohr_model#/media/File:Bohr_atom_model.svg

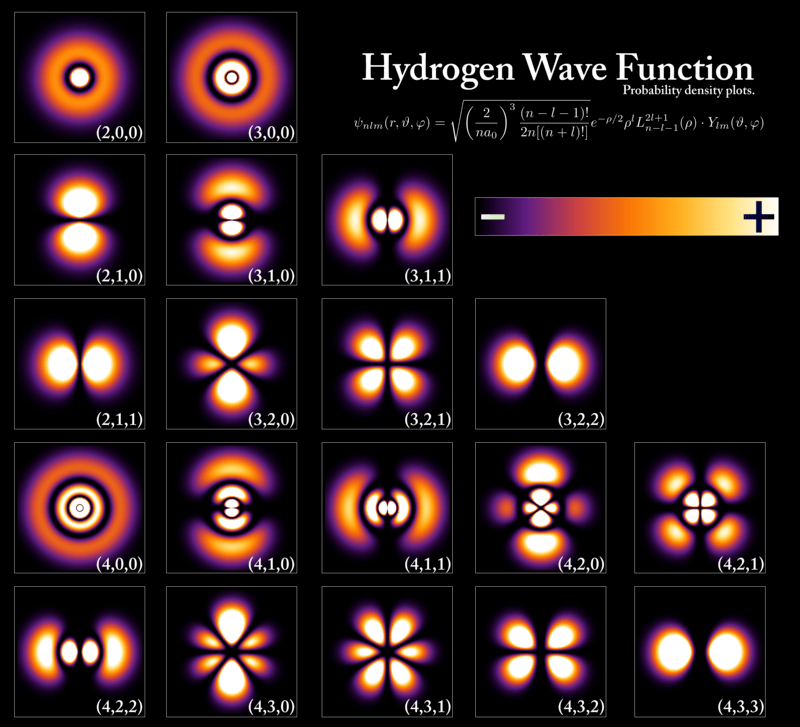

However, the current accepted model of hydrogen – and even atoms in general – is the quantum mechanical model, which explains why there are certain “sublevels” in energy. The electron, depending on the amount of energy it has, forms what we call an orbital – a sort of space where it is likely to be found – around the proton. In its lowest level of energy, the electron’s orbital is simply a sphere – that is, it is likely to be found in a ball wrapped around the proton. However, higher energy levels can lead to weirder shapes: a dumbbell perhaps, or a clover leaf with bulbous lobes (see Fig. 2).

While this is the most fundamental form of hydrogen, it is most commonly found as a molecular gas, H2. It’s when two of these elemental atoms combine their electron orbitals of the same energy, which is preferable because it releases energy. In other words, two electrons would share the same space where it is likely to be found. This “interference” of space is a topic better discussed on an article about quantum mechanics, so we will not delve to deeply into it.

Hydrogen can also have isotopes – meaning, while they have the same number of protons and electrons, they can have different masses. The difference in mass is caused by a differing number of neutrons – a neutrally charged particle added to the nucleus, having almost the same mass as a proton. In its usual form hydrogen has zero neutrons and a proton in the nucleus, and is called protium. But hydrogen with one neutron and a proton is called deuterium, and when it has two neutrons and a proton, it is called tritium.

Uses

Hydrogen can be used in the production of energy in fusion reactions, where two single hydrogen atoms are made to combine so that the protons are glued together by a strong nuclear force that overcomes the repulsive electrostatic force. The electrons then buzz around the newly formed nucleus of two protons. This process releases energy. It is also used in synthesizing ammonia (NH3) which requires one nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms, and is put in mixture with oxygen to make rocket fuel.

Trivia

Due to its simplicity, hydrogen served as the perfect model for how an electron behaves when attracted to a central charge such as the proton. Examine the figure above. The shapes seen there, each assigned with three numbers (n, l, m) are the graphs of each solution to the partial differential equation

Where E is energy, m is mass, ħ is the Planck constant, ∇2 is the Laplace operator, Z is the atomic number, qe is the charge of the electron equal in magnitude to the that of the proton, Ɛ0 the vacuum permittivity constant, and (r, θ, ϕ) the spherical coordinates. Ψ is the wave function that when mapped produces the graphs in the previous figure. This is the Schrodinger equation with an electrostatic potential.

Each (n, l, m) corresponds with a specific solution Ψ to the previous equation.

References

JLab [Internet]. c2020. Newport News, VA: JLab [cited 2020 June 12]. Available from: https://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele001.html.

Silberberg MS. 2007. Principles of General Chemistry 3rd Edition. New York City (NY): McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math. 792 p.

Griffiths DJ. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. 2015. Noida (IN-UP): Pearson India Education. 480 p.

5 thoughts on “Hydrogen”